Mississippi County, AR wins 2020 Big Muddy Cup

If you compliment the leaders of Greater Blytheville, Arkansas, on their steely resolve, they’d know you meant it literally as well as figuratively.

Scroll across member organizations of the Greater Blytheville Area Chamber of Commerce and you’ll see names such as Nucor, Nucor-Yamato, Denso, Tenaris NIBCO, as well as institutions such as Entergy, Mississippi County Electric Cooperative and Arkansas Northeastern College. If they’re not in the steel business themselves, then it’s likely they’re serving the steel industry in some way.

It’s been that way for more than 30 years, going back to when Nucor and Yamato Kogyo formed a joint venture that launched a plant in the Blytheville-area community of Armorel in 1988. Today, Nucor-Yamato has the capacity to produce over 2.5 million tons per year of wide-flange beams and other products. Nucor has three other plants in the area now that produce steel sheet, thin-cast steel sheet and pipe. Nucor accounts for 1,800 direct jobs and more than $750 million in annual gross state product. Nucor’s annual Arkansas production of 7.6 million tons accounts for 28% of the company’s U.S. total capacity.

The late John Correnti launched that plant. “He found such a willing and adaptable labor force for a steel mill, because agriculture was undergoing one of its periodic restructurings,” says Clif Chitwood, executive director of Mississippi County Economic Development. “The mill came along and offered thousands of construction jobs, and they hired many people right off the construction line into the plant, which is something Nucor still does. And the guys started making more money than anyone ever dreamed, because the pay system at Nucor is a low base wage of $12 or $13 an hour, but the average person makes between $95,000 and $115,000 because of production bonuses. It can be up to 200% of the base wage.”

After being bought out by Russian investors at his next venture in Mississippi (which won out over Arkansas because of state incentives), Correnti came back to the area later with a billion-dollar investment in Osceola from Big River Steel, which Nucor fought with lawsuits.

Greater Blytheville, Arkansas, Takes Home the Hardware Thanks to Major Steel Investment

by Adam Bruns

If you compliment the leaders of Greater Blytheville, Arkansas, on their steely resolve, they’d know you meant it literally as well as figuratively.

Scroll across member organizations of the Greater Blytheville Area Chamber of Commerce and you’ll see names such as Nucor, Nucor-Yamato, Denso, Tenaris NIBCO, as well as institutions such as Entergy, Mississippi County Electric Cooperative and Arkansas Northeastern College. If they’re not in the steel business themselves, then it’s likely they’re serving the steel industry in some way.

It’s been that way for more than 30 years, going back to when Nucor and Yamato Kogyo formed a joint venture that launched a plant in the Blytheville-area community of Armorel in 1988. Today, Nucor-Yamato has the capacity to produce over 2.5 million tons per year of wide-flange beams and other products. Nucor has three other plants in the area now that produce steel sheet, thin-cast steel sheet and pipe. Nucor accounts for 1,800 direct jobs and more than $750 million in annual gross state product. Nucor’s annual Arkansas production of 7.6 million tons accounts for 28% of the company’s U.S. total capacity.

The late John Correnti launched that plant. “He found such a willing and adaptable labor force for a steel mill, because agriculture was undergoing one of its periodic restructurings,” says Clif Chitwood, executive director of Mississippi County Economic Development. “The mill came along and offered thousands of construction jobs, and they hired many people right off the construction line into the plant, which is something Nucor still does. And the guys started making more money than anyone ever dreamed, because the pay system at Nucor is a low base wage of $12 or $13 an hour, but the average person makes between $95,000 and $115,000 because of production bonuses. It can be up to 200% of the base wage.”

After being bought out by Russian investors at his next venture in Mississippi (which won out over Arkansas because of state incentives), Correnti came back to the area later with a billion-dollar investment in Osceola from Big River Steel, which Nucor fought with lawsuits.

“Nucor was not happy,” says Chitwood. “But they came, and when they came, it was a huge win for Mississippi County, and it started this whole cycle.”

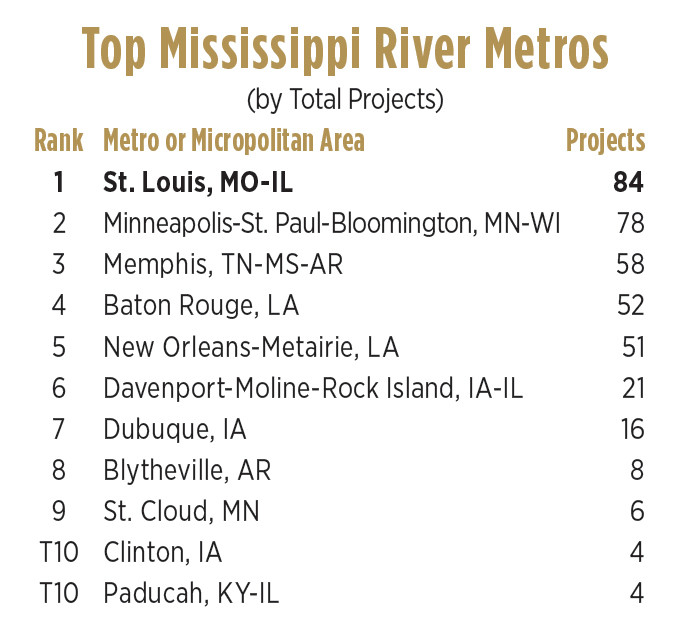

That cycle is the virtuous ecosystem of the steel sector. The projects from those companies are a big reason why the Greater Blytheville micropolitan area — encompassing Osceola and all of Mississippi County — is this year’s winner of the Big Muddy Cup, awarded to the top metro or micropolitan area along the entire Mississippi River for total corporate facility projects per capita.

With eight projects, the area just an hour from Memphis beats out former Big Muddy Cup winner Dubuque, Iowa. The complete list of top 10 Big Muddy Cup communities includes eight micropolitan areas.

Another Magnitude

Since Big River opened, it has since expanded — as has Nucor. That means more people to cut the rolls, to pickle or not pickle, to sell the steel sheets to John Deere, Ford, Caterpillar and a host of other companies.

“I was a little fearful Nucor might decide to pull back from investing,” Chitwood says, “but essentially they began to double down and expand even more. They’ve probably invested close to $600 million to $700 million in new plant and equipment. It’s been a steady drumbeat of one expansion after another, and then the other companies follow.”

“Part of the property Big River Steel located on was actually owned by Entergy Arkansas,” says Danny Games, director for business & economic development with Entergy Arkansas and the former executive vice president of global business for the Arkansas Economic Development Commission. “It’s hard to appreciate the footprint and magnitude of these mills unless you’re intentionally going to them” due to their being on the river and not on I-55. “Mr. Correnti didn’t live to see it to full operation. The last time I saw him, he was giving Arkansas Secretary of Commerce Mike Preston and I a personal tour of the construction site. Even when you get up to the mill, you can’t appreciate the magnitude because you can’t see the depth they had to go to to forge footings. It was a construction project like something you might see on the scale of a skyscraper in Chicago or New York City. It made very large cement trucks look very small.”

It doesn’t hurt that the county is home to the last coal-fired power plant constructed in the United States, in the 1990s. But “the reason they’re all here is the river — because that’s how the scrap comes in — and the rail, because that’s what you have to have to get it out,” says Chitwood. “And I-55 is very close to both Osceola and Blytheville.”

That’s good not only for getting products out, but funneling in the workforce that comes from up to six different counties, working four-days-on, four-days-off like they do in oil & gas territory. Other firms that invested last year in the area Zekelman Industries, which announced in July it will build the world’s largest continuous ERW tube mill in Blytheville adjacent to its existing Atlas Tube mill.

Return to Small Towns

Mississippi County used to be the third most populated county in the state. That was back when overlapping activity came from agriculture, textile mills and the now-closed Eaker (formerly Blytheville) Air Force Base, whose 11,600-ft. runway is still available for use at the now-renamed Arkansas Aeroplex. Times got hard. The formerly full downtowns in Osceola and Blytheville emptied out a bit. But steel has stayed strong.

One thing supporting these growing companies is a half-cent economic development sales tax approved by Mississippi County voters. Chitwood says that raises $3.2 million to $3.4 million a year. “It’s been climbing quite a bit lately, as Amazon and others start turning in sales tax,” he says.

It’s still hard to attract people to small towns. But the region is attracting companies. Some pockets of the area still are struggling with multigenerational unemployment, he says. Others such as Manila and Wilson have remade themselves. But not too much.

“I grew up here, and never thought about needing amenities in Osceola, because that’s what they put Memphis there for,” Chitwood says. “Today people expect and want those amenities much closer and still have small town living. But it’s a struggle to get people to live in a small town. Eventually the world will change, and small towns will come back into vogue.”

Ask the companies and communities in Mississippi County and up and down its namesake river, and you may find that time has come.

“It’s quite an anomaly in Osceola and Blytheville,” says Danny Games of the steel plants. But he might be speaking as well of small towns when he notes, “You have to get off the Interstate to appreciate it.”